The Naples Players turn back the clock in ‘Maple & Vine’

FLORIDA WEEKLY

ARTS COMMENTARY

October 31, 2017

nancySTETSON

[email protected]

An acquaintance of mine bemoans that she was “born too late.” A child of the ’70s, she wishes she had lived in the 1950s instead.

It was a much hipper time, she feels. She loves the clothing, the music, the cars, the look. I suspect she almost sees the era as an extended episode of “Happy Days.”

What she doesn’t take into consideration is how repressive things were back then, the blatant racism and sexism, the taking for granted that women and people of color weren’t equal and should “know their place.” Contraceptive options were limited. Homosexuality was considered both a mental illness and a crime. We were in a cold war with Russia, and schoolchildren practiced hiding under their desks in case of an atomic attack. (As if that would help.)

I thought of my friend the other night when I saw The Naples Players’ production of “Maple & Vine.”

This curious, unusual play introduces us to Katha (Tina Moroni) and her husband Ryu (Dan Bacalzo), a modern day couple living in New York City. She has a high-pressure job in publishing, and he’s a plastic surgeon. They’re grieving Katha’s recent miscarriage, and their marriage is suffering the after-effects.

And then Katha meets a man in a gray flannel suit who looks as if he’s just been transported from the 1950s. Dean (Jesse Hughes) wears pants with cuffs, and a crisp triangle of white peeks out of the pocket of his double-breasted suit jacket. No backpack or man purse for him: He’s lugging a leather briefcase. And instead of a baseball cap, he sports a hat — a 1950s one that goes with his suit, not the kind hipsters wear today to try to look cool.

The two get to talking, and Katha discovers Dean and his wife are 1950s reenactors. Only they don’t do it for just occasional weekends, like Civil War reenactors. They belong to a group called the Society of Dynamic Obsolescence and live full-time in a gated community where everyone lives as if it’s 1955.

There are no cell phones, no cable, no Internet, no laptops. Everyone has to live, speak and comport themselves at all times as if they were living in the mid-50s. (An accidental slip of the tongue or a reference to something modern is considered “a disruption.”)

Katha sees the Society of Dynamic Obsolescence as the answer to all her problems, a safe haven. Ryu isn’t so sure. He suspects it might be a cult, but eventually goes along with his wife’s desires. This change of heart struck me as a little too sudden. I found it hard to believe any doctor would leave his successful practice to work in a factory assembling boxes. But then again, what person, overwhelmed with the pressures of work, family, marriage and life in general, hasn’t at some point longed for a simpler life and a slower pace?

The cost of going back to “simpler times” is more than Katha and Ryu expect, however. Is it more than they’re willing to pay?

Act II is full of surprises, though truthfully, some should be expected. After all, our history is full of examples of what happens, on small or large scales, when people give up critical thinking and abdicate personal responsibility, allowing others to dictate what happens to them.

The Society of Dynamic Obsolescence reminded me of a quote in a WWII thriller I’m currently reading: “Beware the man who tells you he knows what’s best for you; he usually starts by stealing your rights.”

The scenes between Katha and Ryu, and Katha’s scenes at work with employees in Act I, are, unfortunately, some of the weaker moments in this intriguing play. I wish director Bryce Alexander had worked to strengthen those more.

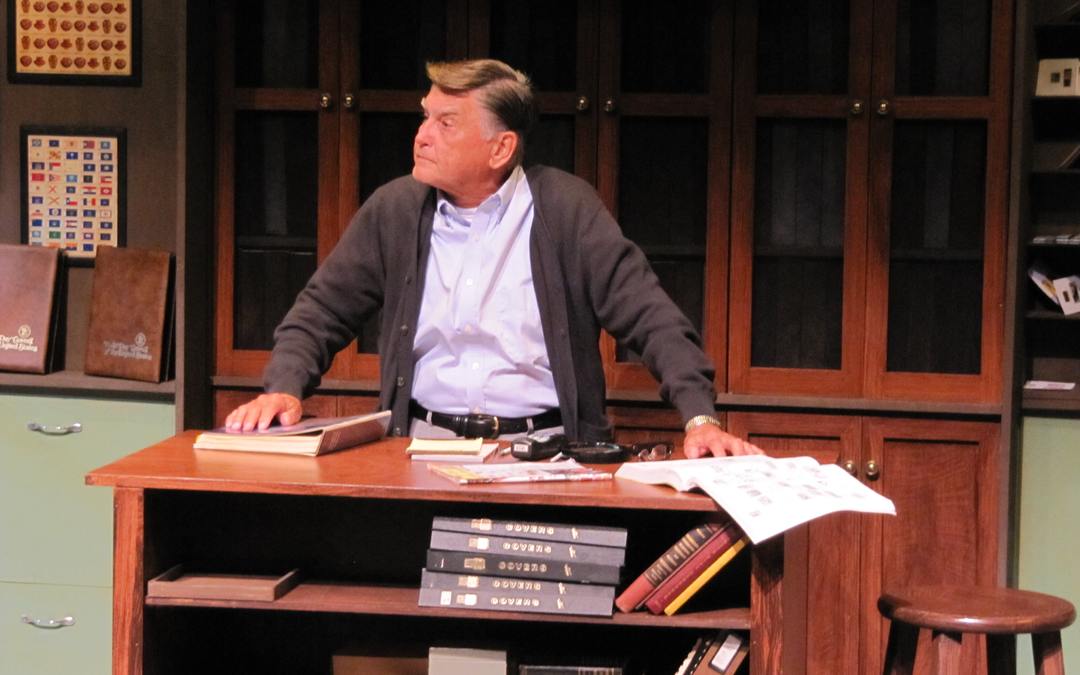

The stage comes alive whenever Mr. Hughes and Jessica Walck, who plays his wife, Ellen, are onstage. A dutiful wife, she stares at her husband with sheer adoration. Ms. Walck plays the role with perfection, chirpy and perpetually cheery. Mr. Hughes’ character is a take-charge kind of guy, a bantam rooster who seems to have something to prove … or to hide.

Ms. Moroni’s character evolves over the course of the play, transforming into another woman than the one we first meet. We see her grow in confidence, though she initially struggles to adjust to her 1950s life.

Mr. Bacalzo’s role is perhaps the most difficult, as we have to believe a doctor would not only give up his profession for manual labor in a factory but also would willingly return to an era where racism is blatant and ethnic jokes socially acceptable.

James Duggan plays two roles: Omar, an arch, flamboyant gay who works in publishing with Katha, and Roger, a stoic, racist factory supervisor in the 1950s world. As the former, he giggles and gossips with Jenna (Ms. Walck’s second role in the play), a ditzy coworker who seems more obsessed with her cell phone and taking selfies; as the latter, he’s brooding and somewhat intimidating and unpredictable.

(And Mr. Alexander provides a nice touch: When Roger and Ryu have a battle of wills and words, Roger slams his much-larger lunchbox down on the table next to Ryu’s, as if to show he’s bigger and superior. It’s a small moment, but clever.)

The outfits, by costume designer Jack Cole, are superlative: suits and hats and ’50s ties for the men; pumps and pearls, pillbox hats and white gloves for the women. Ellen, in particular, looks as if she’s just stepped out of the pages of a mid-century issue of Vogue. And for both actresses, there are numerous costume changes.

As the playwright Jordan Harrison advises in his production notes in his script: “I can imagine a production where costumes and wigs do nearly all the work in transporting us to the 1950s.”

And they do. They are simply stunning. And they do transport us directly to that era.

Chase Lilienthal’s set design assists, especially Katha and Ryu’s new home on Maple and Vine, with teal, tufted love seat with mid-century modern lines and a teak, multi-leveled wall unit with asymmetrical shelving.

There’s a clever scene where Katha is reading “Peyton Place” — a nice nod to the secrets and skeletons in closets that can exist in small towns. But the book was published in 1956, which makes it a “disruption” if they’re supposed to be living in 1955.

But that’s just a quibble. “Maple & Vine” is innovative and thought provoking, an interesting concept well executed. I’ve never seen a play quite like it. ¦

‘Maple & Vine’

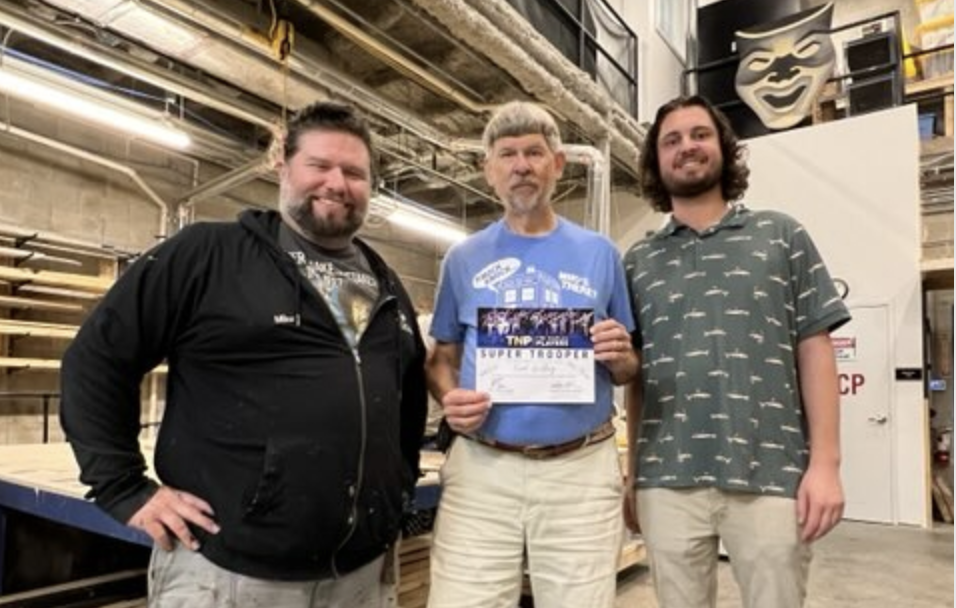

Who: The Naples Players

When: Through Nov. 19

Where: The Tobye Studio at the Sugden Community Theatre, Naples

Cost: $40, $35 Subscribers, $10 Students/Educators. Information: 263-7990 or www.naplesplayers.org

Click to Read full article in Florida Weekly