By Harriett Heithaus

The Naples Daily News

This improvisational theater class won’t teach pratfalls or stage entrances. But the Parkinson’s disease patients who are learning elements of that art with therapist Margot Escott can count on broad smiles and hearty laughter.

There might even be a double entendre slipped in: When Escott, warming up her students’ reflexes with a clapping exercise, urged the first pair of participants to “pass the clap,” she got her first oversize expression — wide eyes — from the entire class without even aiming for it.

That wouldn’t be the last laugh of the day. During the 90-minute improv class, sponsored by the Parkinson Association of Southwest Florida, patients:

- Tossed make-believe balls of different sizes, from pingpong to football, to each other

- Created personality tags for themselves, complete with signature gestures

- Played a sentence completion game as “Dr. Know-It-All”

- Wrapped invisible gifts for their classmates. In one of the funniest sequences of the morning, the giftees then had to describe what they thought their gift was and how much they — perhaps — liked it.

Embedded in this comedy and theater were practice in facial expression, cognitive exercise, movement and sheer camaraderie.

Beneath the laughs

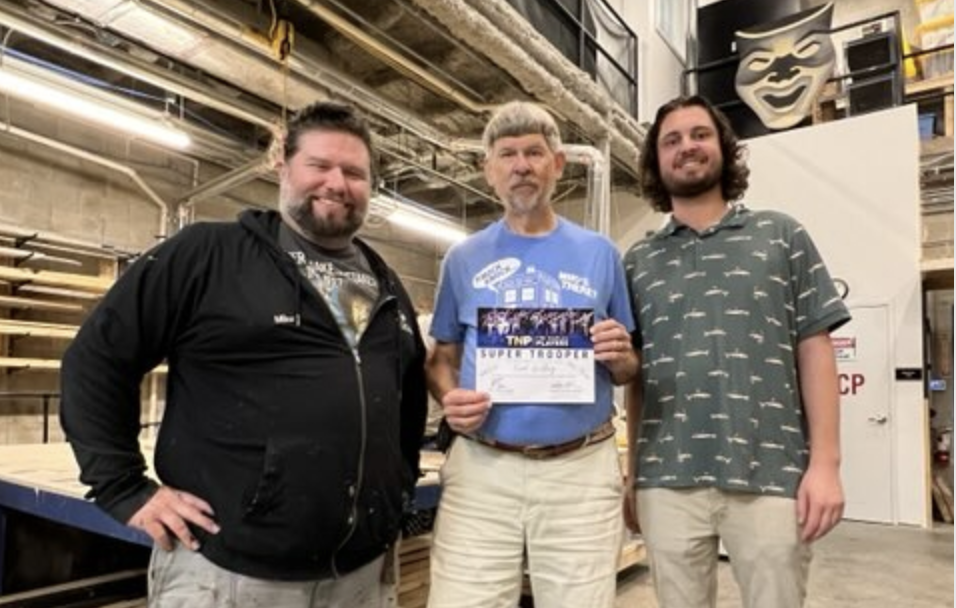

Escott, a social worker and licensed therapist, has studied improv for the four-session Parksinson’s improvisational theater class, one of many she leads for a variety of needs, such as for 12-step addiction programs. She has the good fortune of having a Second City alumnus working with her, Craig Price, director of education for Naples Players, who directs that group’s theater classes for special needs groups. (Both Escott and Price, in fact, are either current or former improv performers; they’ve appeared at the Center for the Arts Bonita Springs.)

Still, as Escott declared to her class, “We are all improvisers.” Students were about to find out how much when each, in teams of three, had to add a word to a sentence to answer questions such as “Why do onions make you cry?” from Dr. Know-It-All.

For a “Five Things” game, individuals had to shout out one-word associations with topics. The word “Naples,” for the record, brought out the descriptives “beaches,” “alcohol,” “warm,” “bikinis” and “Germans.”

“Germans?” asked Escott, flashing a smile. “A lot of them seem to live here,” explained the respondent.

This class, Escott’s and Price’s second held at the Mental Health Association of Southwest Florida offices, had drawn a variety of registrants: Trimble McCullough, a drummer with ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s Disease; Parkinson’s caregiver Clare McKinney, who had come on her own; and Linda Goldfield, executive director of the Parkinson Association of South Florida, among others. Maximum class size is 10.

McKinney is in her 17th year of caregiving, after her husband developed a parkinsonian syndrome following a car accident.

“You lose yourself somewhat,” she explained. “I find I’m freer with him after being here and seeing what people do.”

“I have a big hole in me from not being able to play,” McCullough said. “I was searching for something to fill that. It’s a way to meet people and learn some new things.”

Keith Wang, a retired CPA from Ramsey, New Jersey, who is suffering from Parkinson’s, said the classes had helped his mood: “(It helps me) to be cheerful,” he said.

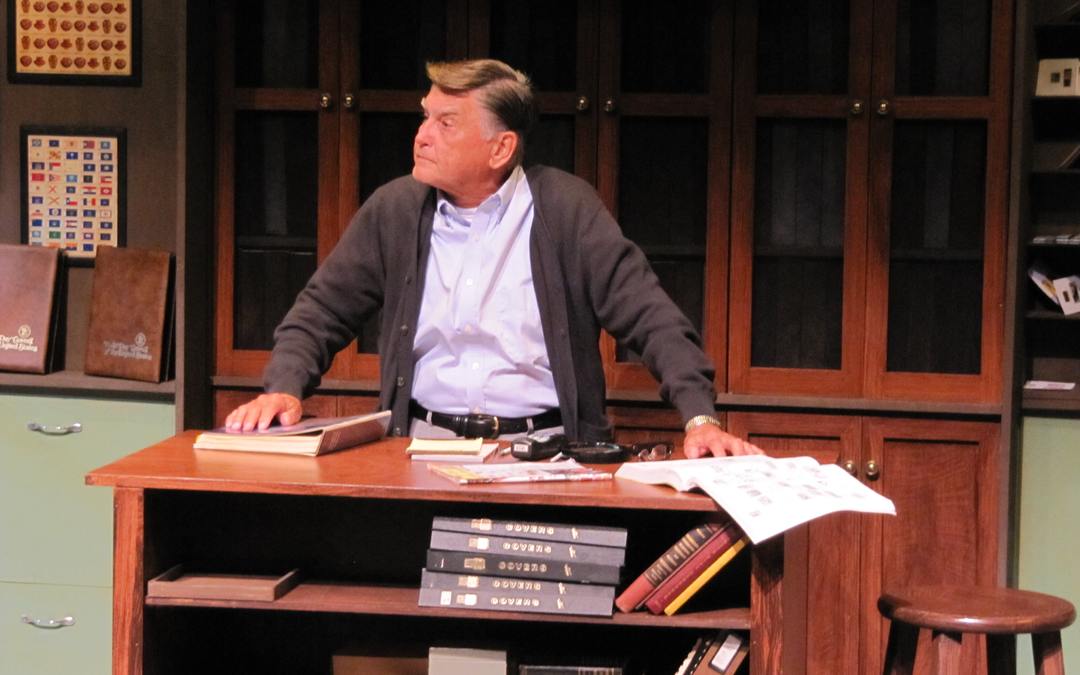

TNP Education Director and LCSW Margot Escott teach improv to people with parkinsons

Study support

Northwestern University conducted a study on two groups of Parkinson’s disease patients who took targeted improv classes developed by Second City, and the findings mirror what the students here say.

Danny Bega, M.D.,assistant professor of neurology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, was the study’s corresponding author.

While he cautioned that the 2015 study was done only on two improvisational theater classes for people with Parkinson’s disease, and research is fairly new in this direction, the results were eye-opening.

More: What researchers learned about improv and Parkinson’s

More: Inventor from Naples makes it easier for seniors to reach the beach

“I think it’s really interesting that people say people with Parkinson’s don’t find things as humorous, that there’s a change in the humor response. It actually makes sense because dopamine is a chemical that’s deficient in Parkinson’s and dopamine is sort of your ‘reward’ chemical that makes you feel good after something funny.”

Yet post-class surveys indicated that may not be true at all, he said. Because of the timing — some patients require more time to respond to events — and the tendency to lose facial expression, Parkinson’s patients may radiate a lower response. But it’s apparently there, he said:

“Part of the disease is they lose facial expression. And people can misread what that means.”

Escott incorporated that into her class, asking students not to answer for others because their cognitive responses simply may be slower. A practice required the entire class to stay quiet for 30 seconds, acclimating them to wait time for responses.

“We’ve got to give everyone their own space,” she told the group.

Bega noted that the Northwestern University study didn’t record a noticeable difference in communication skills after patient classes, but that wasn’t borne out anecdotally.

“A lot of people commented that their communications improved through some of the games that were being played. A lot of the spouses and caregivers would comment that they (the patients) were better able to communicate for themselves at home,” he said.

There was another benefit in offering the improv classes that researchers saw.

“The attendances were great. With different interventions we’ve done, such as exercise, we’ve see dropouts; at time we’ve seen poor attendance. The attendance at this was amazing,” Bega observed. According to the study, 95 percent of the participants attended at least 80 percent of the classes.

“The level of enjoyment they got out of classes was pretty much unanimously very high,” he said.

“They formed a camaraderie among each other that was almost like a support group in some respects,” he said. In fact, he added, the women from one class created their own Parkinson’s support group after the class term.

A comment from class member Adam Paley after the Naples class bore that out.

“This is kind of corny,” he said, “but it helped me realize there are more like me out there.”

Improv for Parkinson patients

What: Improvisational theater class for people with Parkinson’s Disease or parkinsonian syndrome

Where: Sugden Community Theatre, 701 Fifth Ave. S., Naples

When: 10:30 a.m.-noon for six Tuesdays, Jan. 9-Feb. 13; a per-class fee of $10 is available as well

Cost: $50, $25 for members of the Parkinson Society of Southwest Florida

Information: 239-434-7340, ext. 127

CLICK TO SIGN UP